Friday, I went fossicking for a ghost. A report, written twenty-two years ago about my PTSD, which I had not laid eyes on this side of the Howard administration, but whose cover and general aura I could still picture with the obsessive clarity of a lost lover or a particularly traumatic MyGov password reset.

I required it as the final touch in a monstrously detailed backgrounder for my newly appointed advocate, which turned out to be the bureaucratic equivalent of assembling the Dead Sea Scrolls with a broken stapler.

So I did what any rational person with respiratory issues and a paperwork problem would do: I risked life and limb by abseiling into the sedimentary depths of my archived existence, which I have managed to drag from property to property in no fewer than six moves in ten years, and roughly a dozen over the last twenty. An itinerant filing cabinet with asthma.

First stop: the lovely old black Bakelite suitcase, which in my mind absolutely contained important documents and in reality contained clothes that had clearly retired from importance some time in the early 2000s. Next, the modern Kmart under‑bed fabric coffin, a sort of soft-sided mausoleum for unsorted paper, which did indeed contain documents – all of them spectres in an interpretive free‑form dance of chaos.

Triple-masked – including a makeshift terry hand towel folded into a triangle and knotted at the back in proper outlaw fashion which I have recently re-discovered is actually more effective than many commercial offerings - a near absolute triumph of bathroom linen over public health procurement – I began sifting. Every handful of paper was a time‑capsule of catastrophe: letters, forms, test results, all dredging up the twenty‑five-year‑old nightmare that had produced the report in the first place. No report.

The only remaining plausible location was outside: the weatherproof storage container disguised as a garden bench, which sounds charming until you open it and discover it is, in fact, a horizontal landfill. More paper. Unspeakable paper. Journals, diaries, receipts, forms, correspondence dating back to 1984, all mingling in a kind of organic taxonomic compost. Still no report.

After about 90 minutes of this archaeological despair, I relented to try and find it buried in some file in some folder somewhere on my computer. This, one would think would be the easiest place to check first and, the last place I wanted to, but there it was, instantly locatable; I had, of course, thought of using it initially, but had been determined to find the hard copy to scan it, presumably for the tactile satisfaction of suffering in multiple real-world processes.

The digital version, however, came with its own personality disorder. I had forgotten that I had wrestled this particular PDF before until it started repeating its old tricks. Reading it was like attempting to negotiate with an especially deranged middle‑management bureaucrat accusing me, with escalating hostility, of leaving too many mugs in the office sink. “I don’t even drink tea, coffee or Cup-O-Soups at work”.

It was a 250‑page PDF golem: police reports, medical reports, letters to the Director of Public Prosecutions, the Premier, the Medical Board of New South Wales (now operating under some new brand alias to suggest improvement), the NSW Ombudsman etc – the full chorus line of agencies that specialise in solemn head‑tilts and procedural inaction. The thing existed because I had dared to lodge a complaint demanding accountability for precisely that inaction and some recognition that the harms it produced were, in fact, harms, and not – as is so often implied – “teachable moments”.

The word victims is right there in the agency’s name, which one might naïvely interpret as a hint that they understand something about the needs of, well, victims. Brand identity of course does not equal insight; In mine and too many others cases it is clear they have been inoculated against it.

Having resigned myself to the digital, I knew the three-page report I needed had to be buried somewhere inside this 250-page chimera. No OCR. Of course there was no OCR. Why on earth would a government record in the twenty‑first century be text‑searchable? Instead, each page had to be viewed manually, like some medieval manuscript.

To add insult to the tedium, the file itself was corrupted in a way that felt almost performative. You would scroll down a page, watch the text appear, and then, as you continued, it would simply vanish. Scroll back up, and the page would now be blank, as though the document had decided retroactively that you were not authorised to recall what you had just read. Printing it was an even more avant‑garde exposition: some pages produced text, others emerged as spectral whiteouts. It was less a document than a psychotic episode in selective redaction.

In retrospect, this is clearly why I wanted the hard copy – somewhere in the back of my mind lurked a memory of spending hours trying to strong‑arm this file into behaving before. I had already tried the entire exorcism liturgy: re‑exporting, re‑saving, uploading to various PDF fixing tools, copying, pasting, screenshotting – every ritual short of sprinkling holy water on the laptop.

What should have been a simple extraction of three pages from a single file became a further 90 minute episode of The Digital Peculiarities of the State, featuring your host: Me, Again, Still Here. Page by page, click by click. A testimony to what happens when systems designed to address injustice end up perpetuating it in .pdf format.

And yet, trudging through the entire thing had an unexpected payoff. As I went through page by page - for the first time, searching for the report, I realised something astonishing: the document that had been created to determine a very specific point – did not, in fact, contain that point - The Determination. The closest it came was a copy of an Interim Determination about the point. But where was the point?

It had everything else. Every tangent, every peripheral observation, every procedural footnote, even a $25 cheque stub from an engaged lawyer. But the actual Determination itself – the central answer, the point of why it existed – was simply not there.

I suppose it's more plausible to blame the file’s malfunction than admit the one crucial piece was deliberately omitted from the start. Who can say?

Fortunately as well, in my initial archeological expedition I had absent mindedly retrieved about ten other 'important' documents, "just in case I need those later". Among them, after a bite to eat, I later found the original hard copy of the Determination. An unfortunate one but nonetheless here it was - a mini miracle of sorts. Yippee! My reverse ordered logic had actually paid off.

Even skimming it to minimise triggering a PTSD attack confirmed the absurd reasoning they'd used to determine the point. They'd determined that the acts of violence as an adult had occurred "on the balance of probabilities", but had rejected that the same acts of violence by the same anaesthetist at the same hospital when I was 15 could not be substantiated. They argued that two incidents separated by six years didn't constitute a pattern, regardless that the second incident contained four identical assaults.

Their 'pattern' definition also excluded the defendant's modus operandi — he'd done exactly what he did to me to another unfortunate soul nearly 20 years prior and was convicted for it.

In essence, they'd sidestepped determining whether an act of violence against a minor had occurred — a far more legally reprehensible crime, one would think — and instead prioritised that the assault which occurred in adulthood was bureaucratically more palatable. This was because I could not establish, in their eyes, that the act of violence at 15 had contributed to my C‑PTSD. Ludicrous! No wonder the Determination isn't in the digital file.

The grim irony is, that this lack of a definition of pattern speaks more about their pattern. I was generously offered the opportunity to take the matter to the District Court by my lawyer to establish precedence about the definition of pattern in this context - but I had to move.

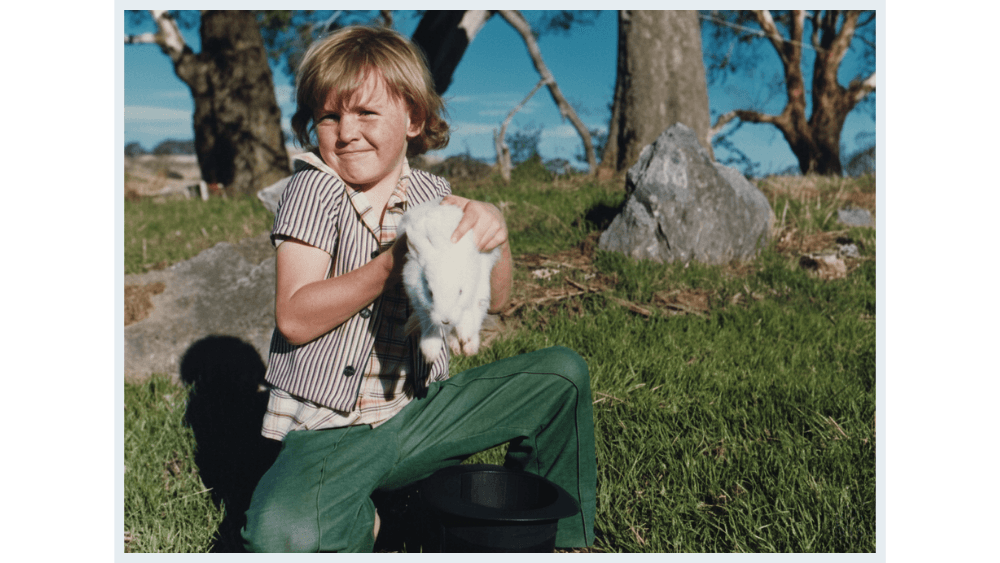

Like one of those childhood magic sets where the “illusions” are lavishly packaged in an oversized black box but turn out to be disappointing cheap, brittle bits of brightly coloured plastic that are in no way capable of producing a truly convincing deception, this was their magic trick.

Am I missing something here?